The Baldur's Gate 3 "Game Standard" Dialogue Highlights A Lost In Translation Issue

The BG3 debate shows that games development has a language that necessitates better understanding and certainly, education.

There’s been a lot of buzz lately surrounding the recent release of Baldur’s Gate 3, the highly-anticipated third installment of the party-based RPG backed by the beloved Dungeons & Dragons system and world. It released after three years in early access a couple of weeks ago to massive acclaim and as recently as 3 days ago, new records for concurrent users (CCU) I’ve personally not had a chance at it yet, mostly because I fall more squarely into the JRPG realm of preference over strategy/tabletop-style RPGs like this one, though I did play a bunch of Baldur’s Gate 2 back in the day, and enjoyed what I experienced of it.

With this success, however, has come a rather heated discussion surrounding the current standard of games. The primary source for this was an IGN video that was posted that purported that the amazing reception that Baldur’s Gate 3 received should spur questions about why other studios cannot do the same.

I’m going to set aside the whole talk about the validity of what the IGN video used as context to make their point, or about whether or not its posting was responsible - other people have done that for me already. And I’m sure that by now, every nuance of the core issue it brings up (the “standard for games”) has been done to death.

Instead, I want to highlight something that could be improved upon when talking about this issue and others related to game development/feedback, and that’s in translating what’s being said into meaningful and useful info, something that YouTuber Jesse Cox appears to show above when posting his own video about the recent debate. In essence, it boils down to the fact that valid sentiment often gets lost as people talk past one another when it comes to games.

I have a soft spot for the “Ocean’s” movies, and one of my favorite and funniest scenes is the one in “Ocean’s Twelve” where Rusty and Danny take relatively inexperienced (yet eager) Linus to a business meeting. Linus has insisted on being included despite not knowing the ins and outs of planning a heist, and struggles with trying to understand the bizarre language Rusty, Danny, and the contact, Matsui, are using with one another. Linus’ attempts to muddle through the exchange and keep up are said by Rusty and Danny to be a complete disaster. Near the end of the movie, it’s revealed that the entire exchange was an elaborate prank on Linus, a way of having a little fun with him as a first-timer.

Oftentimes, I see some players fall into the same trap that Linus does. They witness or see dialogue between game developers or statements made by them, and make a supposition that they have the same understanding of what’s being said. Terms like “polish”, “release-ready”, or even something as simple as “bug-fixing” are oftentimes thought of or used by some in the games community as simple things in definition, when in fact there is a lot of nuance to what those terms mean or are implemented - which of course, extends itself to their perceived understanding of game development as a whole.

If “polish”, for example, is understood by players to mean “as much time as it takes to be 99% bug-free”, but in reality is oftentimes “a reasonable amount of time, given limited budget and development milestones, to not have major bugs”, those are two entirely different things. If “downloadable content (DLC)” is thought of by gamers as “a way for studios to make more money from players by withholding content” but is oftentimes “content that was cut from the original development timeline to hit a release date or allow more time for iteration”, that’s also a differing definition. The list goes on. The point is that it’s never as simple as flipping a switch to not make the kinds of choices that lead to perceived-to-be “bad game” releases. Just like any language, there is a level of nuance and context given when communicating in game development terms and ideas.

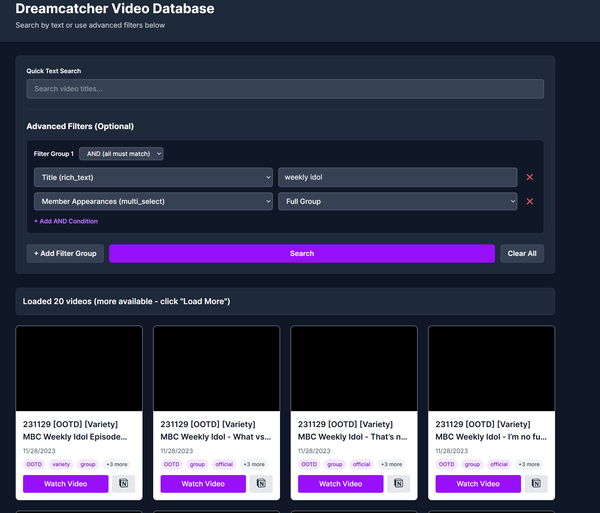

@writnelson#baldursgate3 #gamedev #behindthescenes

Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

But don’t get me wrong - I’m not saying that gamers bear the whole responsibility of understanding (and not losing in translation) the language of game development. Game development studios should also be doing their part to communicate the nuances of that language and what goes into making games, because to a lesser extent, developers may also misunderstand and, like Linus, lose player intention and valid feedback when witnessing and attempting to participate in certain statements and discussions between them, such as accountability for time investment for large studios, and properly communicating with and taking into account player opinion.

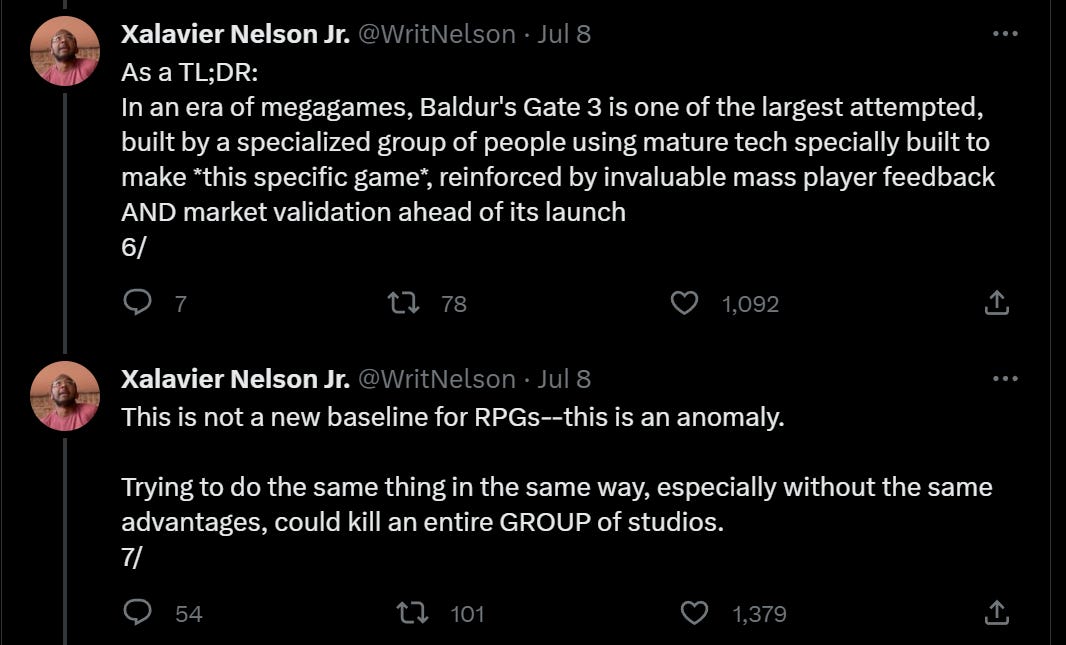

Ultimately, education will likely be the key to avoiding “lost in translation” dialogue in the future. Indie developer Xalavier Nelson Jr., whose Twitter thread on the standard of Baldur’s Gate 3 ironically served as a flashpoint of the conclusions made in the IGN video, has been great not only in full context of the thread in question but engaging in follow-up with his community of followers after that (and that was even before the IGN video was posted). As such, the example Xalavier provides should be one that is duplicated if at all possible. Ensuring that people understand what it means to have a budget behind your game, what it means or is supposed to (or not) guarantee in terms of the outcome of developing that game, and more are all resources that can and should exist for gamers. Places like the free portions of the Game Developer’s Conference vault should be more widely distributed and referred to (and, in my opinion, not be limited just to GDC). Historical videos such as the one-time Extra Credits (now Extra History) feature “So You Want To Be A Producer” should be modernized elsewhere and distributed by credible members of the game development industry. There’s a bunch that can be done, but it probably starts by doing research over being reactionary.

As for Linus, for those of you that don’t know, by the time the end of the third “Ocean’s” movie rolled around, he’s seen as having come far from being a rookie in the first movie to being pranked for and making mistakes in the second to being seen as on more equal footing with one-time mentors Rusty and Danny. He makes a calm and collected exit, having learned and known more about what it means to work in the profession that they do. My hope is that folks follow the Linus arc in listening (and sometimes erring in doing so), learning, and being better at understanding the “language” of game development and the feedback that surrounds it. A better understanding of the process, and more importantly, the nuance and context, can be nothing but beneficial to everyone. It’s certainly a long-term goal, but one I hope can be worked on to avoid messy (and often unproductively inflammatory) discussions about the industry in the future.