Dreamcatcher’s Dystopian Fight Against Hatred In K-pop and Beyond

How K-pop’s resident rock/pop girl group built a world in their latest songs with a societal message against the language of hate.

“Including people of our profession, lots of people are hurt by words. I want people to be more careful about what they say.”

Distilled into two sentences stated by group leader JiU in a February 2020 interview with News1, the goal of why K-pop rock/pop girl group Dreamcatcher built an entire “Dystopia” to tell stories through their latest songs seems like such a simple and achievable ideal. In the sometimes bright and sunny world of K-pop, stories and worlds in music videos can often take a back seat to hard-hitting visuals (whether they hit a “cute”, “sexy”, “stylish”, or other such standard conceptual chord), impactful vocals, or choreographical mastery. But Dreamcatcher, true to their calling card of being a K-pop group with a unique story, wants to do more than just grab you with their concept, skill, and presentation. They want to tell a story, build a world around that story, and then through those, help send a message to society. That message, by the way, tackles an issue that we who play with and work in games would colloquially call “hard mode” difficulty — that of hate commentary and the dark, sometimes fatal power it can wield in hurting others.

Part of the reason this can be extremely difficult to talk about and try to address is the straight-up enormity of the issue, especially as the advent of the internet and its ability to cloak the worst of its participants in a consequence-free aura of anonymity in the midst of a (mostly) faceless audience. Hate, especially hate that’s communicated online can have an exponentially devastating effect on its targets, even more so when those targets work in a front-facing, constantly spotlighted industry like that of K-pop. In recent history, the hateful nature of words online and how the carelessness of how they are used has affected artists in the K-pop sphere in some of the worst ways. Aside from some discussion that has come up in the midst of the flashpoint of terrible events (one of which we will explore in this article), there isn’t really an easy solution that presents itself. It’s a nice idea to say you want people to be more careful with their words, and another to try to get people to do it.

In this article, we’ll take a deep, comprehensive dive (and I do mean deep, hope you have some time to read) into both “Scream” and “BOCA”, and also take a peek into what might be in store for “Dystopia” part three - but not before providing a bit more context into just why hateful commentary as it relates to the K-pop industry has been a difficult, even uncomfortable, issue to address.

The dark side of K-pop’s passion — turned against its artists.

[CW: Suicide, self-harm, physical violence, sexual abuse — if on the web, you may skip over this by clicking this link to the “Scream” section. Otherwise, scroll past.]

In any other context, even in the world of K-pop where idols sometimes live stream late at night with fans before bed, this would seem to be a normal signoff, a farewell to sleep before a new day brings with it new opportunities to connect with fans even in the midst of a packed schedule that seemingly only artists in the industry can shoulder. But for Goo Hara, once a member of one of K-pop’s most prolific and popular girl groups in KARA and now a solo artist trying to make her own way in the entertainment world, they would turn out to be her last, taking on a haunting finality. Hara would be found dead hours later, with the police concluding no suspicion of criminal activity. The signs would later point to an apparent suicide.

The tragic fate of Goo Hara was in part the culmination of several events in the past two years that had severely tested the 28-year old idol’s mental health and well-being:

- The denial of suicide attempt rumors through overdosing on pills (clarified by her agency at the time as a treatment for sleeping disorder and indigestion)

- A physical altercation with a drunk ex-boyfriend in 2018 resulting in injuries to Hara’s lower leg, uterus, vagina, cervix, face, and more, a fight that her ex-boyfriend would later claim was a one-sided affair.

- The threat of blackmail via leaked sex tapes by this same ex-boyfriend, and a subsequent investigation where separate charges were to be brought to both him and Hara.

- Having to defend herself for getting plastic surgery to deal with a drooping eyelid.

- A reduced, then suspended sentence in the trial of her ex-boyfriend, after being found guilty of intimidation, assault, coercion, and property damage. The trial would have the consequence of Hara’s Korean agency not renewing her contract.

- The loss of Hara’s close friend Sulli via suicide, another fellow K-pop idol whose outspoken nature made her the target of constant online harassment that likely contributed to her untimely death.

“We suffer from things that we can’t even tell our friends and family. It’s something that no one can understand even if talk about it.”

It’s not like Goo Hara was unfamiliar with hateful comments being posted about her. Following the disbandment of KARA, a five and later four-member girl group that reached the heights of K-pop popularity, Hara’s foray into a solo career wasn’t always met with positivity. In response to news that one of her solo tracks was unfit for broadcast, one commenter stated “She has singing skills worse than even a commoner and she’s releasing a solo?”. Another wrote, “Ha ha ha she can’t sing, dance, or rap so she’s obviously pushing for a provocative concept but she won’t even hold a candle to Hyuna”. The harrowing and difficult events of 2018 and 2019 didn’t stop the hatred from pouring in, with accusations of bribery and dishonesty coupled with the misogynistic shaming we’ve come to associate with those speaking out as victims of assault.

The constant harassment led to a suicide attempt by Hara in May of 2019, only prevented by her manager discovering her and bringing her to the hospital. Though she would reassure her fans (and inexplicably apologize for the incident), attacks on her for her admitting to depression and mental health issues continued, leading to Hara resolving to take legal action against malicious commenters. In a statement both resolute but also imploring, she wrote:

“Public figures and celebrities are not people who simply gain things [without trying]. We have to be careful with our private lives more than anyone. We suffer from things that we can’t even tell our friends and family. It’s something that no one can understand even if talk about it.”

Still, the hate comments continued, persisting all the way up until Hara’s untimely death in November of 2019.

But the pendulum swings both ways. Just as that intensity can be harnessed into a passion that is most commonly displayed in praise, promotion, and emotional support for chosen idols and groups, so too can it be employed in condemnation, degradation, and emotional destruction towards those same people. The most common way in which either of these is conveyed is through verbal communication and our language, often anonymously, behind a mask of secrecy.

This duality, this potential of both dark and light, black and white, good and evil as it relates to the words we use is the essence of what Dreamcatcher employs to drive their “Dystopia” story, world, and ultimately, the message they’re sending to society.

With this context firmly in hand, we can finally take a look at how the “Dystopia” series title tracks, “Scream” and “BOCA”, convey this message. There’s been a lot of theorycrafting around the internet about these videos and songs, but I’m hoping my contribution, supported by interviews and direct quotes from Dreamcatcher, will help lend some credibility to what I’m putting forth.

“Scream” — corruption, witch hunts, and an awakening.

“Scream” is the first visualization we get of Dreamcatcher’s “Dystopia”, and is the beginning of this look into the world that it builds. The presentation in the music video is dark, filled with cloudy, lightning-filled skies, a foggy, purplish miasma, and what appears to be a blasted, barren landscape filled with dead flora, collapsed and broken columns, and continuously stirred-up dust and sand.

The idea is that there is a tree that bears white fruits when people say positive words, but bears black fruit when people say negative words…we serve as the tree spirits that protect the tree to purify the black fruit.”

I’ll talk more about what JiU says about their role in a bit, but this core concept - the idea of negative, hateful commentary leading to a corrupt and dark world is, I would put forth, part of the primary warning Dreamcatcher is delivering to society, one which includes the K-pop fandom that is very close to their profession. Negativity and hate, even delivered through something intangible as verbal and online communication, has a very tangible, real consequence to the world at large. What’s great about having a music video to show this is that you can actually visualize that on the screen, something which “Scream” does brilliantly.

Most commonly these campaigns are directed against those with unpopular opinions, but as we saw in the tragic story of Goo Hara, you can be targeted simply for being in the public eye and doing something thought of by a largely anonymous group to be wrong. On a variety of levels, what happens to victims in a witch hunt is a core part of the “Dystopia” world, as JiU remarked in an interview with the Korea Times:

“Witch hunt is linked to Dreamcatcher’s musical universe…Since a witch hunt is also about hurting people with words, we thought it was connected to us…But we believe anyone could fall prey to a witch purge in their life”

So how does this tie into what we see and hear in “Scream”? Let’s take a look at how both in the visual action and in the song the signs of a witch hunt are shown.

JiU’s already mentioned that the role Dreamcatcher plays in the video is as “tree spirits”, apparently responsible for the stewardship of the Tree of Language. In the beginning, the video has several shots of Dreamcatcher sleeping, supposedly dormant and unneeded — that is, until people corrupt the Tree with negative language, throwing its balance completely towards the darkness.

It’s towards the end of the video, but I’d put forth that the shots of Dreamcatcher waking is what happens immediately after the Tree is severely corrupted. The point is that Dreamcatcher, as guardians of the Tree of Language in this music video, sees something is wrong and attempts to deal with it.

This, however, is where the witch hunt theme presents itself. The corruption, symbolized by the negative words and language put forth by people who “forgot how to say good things”, attacks Dreamcatcher, and resists attempts to purify it. You can see this in several visual shots in the video, the most obvious being when Gahyeon attempts to touch the purplish, corrupted core of the Tree of Language, only to have it shatter.

Other shots include Yoohyeon being chased through the landscape and isolated in an empty ruin, SuA running into the Tree’s sanctum pursued by an unidentified smoke she eventually has to defend herself against, and Siyeon lost in a purple fog. All of these serve as visual aids to show how both symbolically and literally, the negative words now intertwined with the corrupted Tree go on the offensive against Dreamcatcher’s tree spirit characters. If it sounds like an analog to how negative, hateful words can be weaponized against the target of a witch hunt (either figurative or literal), that’s exactly what it is.

This is where the lyrics of “Scream” come in. According to Siyeon in a Show Champion Behind interview, “both in the lyrics and the performance, there are a lot of things you can relate to if you’re a modern person”. Much of the core of what’s relatable surrounds how Dreamcatcher is singing about how they feel persecuted or harassed by people using negative words, something which they hope others can relate to and understand. JiU referred to this idea in the News1 interview by remarking that “we know there are lots of people who get hurt by hate comments and by words, so we want to do a deep dive into that.”

This is the majority of the lyrics of “Scream” — a mix of bewilderment, hurt, and suffering due to being attacked and singled out in the midst of a witch hunt. Here are some examples:

The cold wind blows/I can feel the stares

All pain flowing through my veins

My tied up hands/this numb feeling

Although everyone throws stones at me

I can’t escape

A trick behind a mask/a ridiculous freak

A random target created from the increasing hatred

s like a sharp blade

Even though they wound me and dig into me, my breath can’t stop

I can’t even tell who this is for/Someone please tell me

Within the rising smoke now/Please I don’t want to scream

Combining this with the visualization, the “story” of the music video, and the choreography (with one such example pictured above), “Scream” bombards you with imagery and lyrics which depict a world in “Dystopia” where anyone can be targeted with hate comments as a “witch”. Additionally, on the other side of the coin, what’s also being said is that anyone can be a participant in that targeting, due to how easy it is to remain anonymous and produce hateful comments. The recurring image of someone behind a faceless mask is used in “Scream” to represent this sinister, harmful element that Dreamcatcher is trying to defend against, both in the video’s story and as they stated in a News1 interview, in their lives as idols:

(Gahyeon) “I actually cry when I read hate comments. Even the smallest comments can feel significant or insignificant depending on context, so I cried.”

(Dami) “Though we’re told not to see them, they’re very visible so it can hurt sometimes. So I try to look only at the positive posts and find comfort in the people around me.”

With all of this being thrown at listeners of “Scream”, and the dire warning that this exists not just in the fantasy world of “Dystopia” but in actual real life, where it’s happening even now, the message might seem a little pessimistic. But the last part of the lyrics of “Scream” as well as some of the remaining imagery we haven’t discussed yet, provides a small beacon of hope.

That hope comes in the form of a sort of awakening or awareness, and you can connect this idea through a few things in the lyrics and visually in the video. The first image that shows this is through the witch’s depiction through the mask carried by and used by Gahyeon and shown in other shots in the video.

Indications that this specific mask is meant to be the “witch” or target of the witch hunt are seen in the left eye bleeding, a callback to JiU singing “My covered eyes are stained with blood” at the beginning of the song, and the mouth sealed with what appears to be chains, a potential reference to “please I don’t want to scream” in the chorus.

But the most telling sign visually is the open eye, one which is shown not just in the mask, but in the lyrics and iconic motion performed by Dreamcatcher in the video and choreography, that of “Devil eyes come/I open my eyes”, performed by showing one eye closed, and then the other opened with a specific gesture that looks like devil’s horns.

The “devil horns” gesture, a bit of a nod to Dreamcatcher’s rock origins, has been a bit of a misunderstood one. It doesn’t actually have much to do with the devil or the evil that the same devil represents, but quite the opposite — it’s a warding gesture against the evil eye, as explained by Ronnie James Dio of Black Sabbath, who popularized the gesture.

As it relates to “Scream”, there’s a kind of ritual chant-like nature to the “devil eyes” portion of the song — it’s spoken, not sung, by both Dami and Gahyeon, and to me, appears to be both an attempt to ward against targeted evil, but also open one’s eyes to it, to be aware of it, and perhaps, to not be so fearful of it.

It’s that transition, that realization, and that awakening in both the lyrics and the music video, that appears to bring the song to its conclusion, which is part of why the “awakening” shots of Dreamcatcher come near the end despite arguably belonging at the beginning of the video chronologically. From the bridge to the end of the song, the lyrics depict the targets moving from a passive role (as a victim) to an active one, someone who has agency in determining their own fate and who accepts who they are. “Please I don’t want to scream” becomes “I just wanna make you scream”, and there’s a resolution to move forward.

After everyone departs, I open my eyes again

The disappeared traces/can’t believe me

Don’t be sad no more, no more, no more

For me no more, no more, no more

Forget everything you’ve seen, believe nothing happened

And one by one everyone goes crazy

I just wanna make you scream

Regardless, there is nevertheless a transition in the lyrics, and you can see this on both literal and figurative levels. In the story of Dystopia, Dreamcatcher, as tree spirits, endure the negative attacks from the corrupted words in the Tree of Language and walk away from it, resolving to find another way to purify it and its black fruit. In the metaphor of the witch hunts we see in today’s K-pop industry and beyond, there’s an encouragement that victims of a witch hunt, despite enduring a stream of continuous, hateful comments, can find strength in rejecting their effect, in walking away from them, and in realizing you should be comfortable with who you are and be proud of it, even if some people may vilify or persecute you for it.

On some level, Dreamcatcher has already found ways to deal with hate comments and potential witch-hunts directed at them. In their CBS nocut interview about “The Tree of Language”, SuA takes heart in the fact that “there are more positive comments than [hateful] posts like that”, and JiU adds that “The fans are good about reporting hate comments. Then, I realize that ‘ah, there are people on my side’.” Yoohyeon commented in the News 1 interview that “There are many fans who write long letters to us. There was one who said they found some energy thanks to us while battling depression. That energized me.” It’s definitely encouraging to hear these testaments to Dreamcatcher’s mental strength under such scrutiny.

When we see Dreamcatcher in the second video in the “Dystopia” series, “BOCA”, we return to a Dreamcatcher having gone out into the world at large to do what’s needed to help purify the Tree of Language. The main difference to note here is that rather than take a passive role, Dreamcatcher picks up where they left off in the last portion of “Scream” by taking on a more active part in dealing with hateful language.

As with “Scream” there are multiple levels where this is taking place. In the story of the music video, this is accomplished through an effort to purify the Tree through both cleansing water while also being out in the world protecting victims from those who are anonymous and hateful. In the context of Dreamcatcher’s societal message to the real world, this is done by communicating the notion of a hopeful, supportive message to those who’ve been victims of hate comments, and a resolution to stand against those who employ them. We’ll look at both in the course of breaking down Dreamcatcher’s “Dystopia” in “BOCA”.

One of the interesting things about watching “BOCA” is seeing how Dreamcatcher’s portrayed characters have changed ever so slightly. JiU clarifies what’s happening here in the group’s NaverNOW “5 Minutes Before 6” radio interview 20:50 minutes in:

The story continues from our last song, “Scream”, and is the second installment of a trilogy…Dreamcatcher as water priestesses work on the purification process. In “Scream”, we depicted a world tormented by hate comments. And now, we start purifying it.

Here we see that Dreamcatcher has changed ever so slightly from being tree spirits. Now taking more of an active role and determined to purify the Tree through other means, they decide to do so in part through rituals involving water. Water has long been a cleansing, healing symbol in religions, literature, and in other similar areas and its most literal of interpretations, can be seen as washing away of dirt, grime, or in this case, the darkness of corruption that sits in the world of Dystopia.

Multiple images depict Dreamcatcher in their role as water priestesses working with the water to try to purify the Tree of Language which, according to Siyeon in the “5 Minutes Before 6” radio interview at 42:15, “used to be so big in ‘Scream’ [but] got hurt so much that it gets smaller…it’s so upsetting”. We see the Tree, much reduced in size and with only a small number of white flowering fruit in the background, with Dreamcatcher in multiple shots working with water to try to help it along — SuA performing a flowing dance in the rain, Yoohyeon working with a body of water with air bubbles, and JiU sitting amongst its blossoms and running her hand through the water pool.

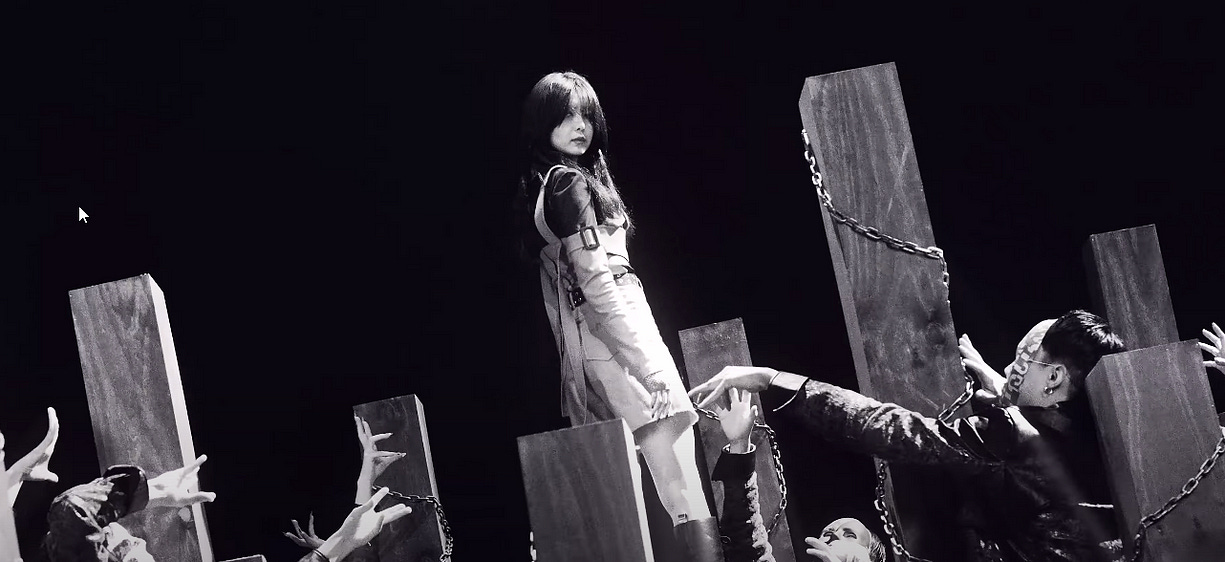

The other way that we see Dreamcatcher play a role is in a more confrontation with the source of the hateful language that has corrupted the Tree of Language — those faceless, anonymous masses that make such comments and are depicted in several scenes where they are shown masked, distorted, and sinister. In the music video, we see this in the urban setting scenes, where Dreamcatcher, in a modern styling of clothing you’d normally see in a cyberpunk-style movie, appear to be out in the world of “Dystopia”, standing against these unidentified wielders of hateful words.

The music video shows multiple examples of this. Dami coolly stands up to a hateful, masked mob. JiU strides fearlessly past what she perceives to be an evil, anonymous force and turns to face it as it stares. Siyeon is chased by another malicious and unidentified entity, ensuring it doesn’t latch onto a weaker target. All of this is tied together in a more active role Dreamcatcher takes that I can only define as protector or defender, not just standing in the way of the hatred of the anonymous mob but neutralizing them. Part of the mechanism by which they do this is what SuA in a Show Champion Behind interview refers to simply as locking up and shutting their mouths (hence “BOCA”, the title meaning “mouth” in Spanish):

In an era of irresponsible and destructive words, for those who’ve been hurt, it’s a song that conveys Dreamcatcher’s message of hope. We’ll lock up the mouths of those who say bad things so they can’t open their mouths again!

We’ll get back to the message of hope SuA mentioned in a bit, and for now, focus on the idea that shutting the mouths of those that post hate comments is the method Dreamcatcher is using to more directly affect their attempts to purify the Tree of Language. You can see this theme on multiple levels.

In the action of the video, images show these attempts to silence or shut mouths that are using hate language. Siyeon is surrounded by statues she has essentially muted. Dami, in the earlier shot I’ve shown you, has chained the hate mob to columns and in another, put them behind a barrier where they struggle to get free. Gahyeon attempts to shut mouths up through sheer force of will, suffering as the process of purifying them is a painful one, something she mentions in the “5 Minutes Before 6” radio interview at 42:50.

Finally, in the lyrics, we see much of this “protector” attitude from Dreamcatcher, as they talk about shutting down the mouths of those who talk hatred, shielding the more vulnerable from being hurt.

The thunder crashes heavily

Let it fall, drop thunder

I’ll walk towards you and close that BOCA

…as well as Dami’s raps, which, combined with the visuals in the music video, cast her in a bit of a warrior’s role holding back the mob:

I’m a geek the big paradox

In short, a killer who protects you

Everybody starts to beg when they see they’re in hell

But their mouths end freeze up.

…

Get the key, I’ll set you free

Stop playing hide-and-seek

Follow me closely more, more, come on

Lock the door, lock the door

you fill your precious time with so much hatred?

Too many angels dying now

I’m gonna change your mind

So you’re able to breathe again

This is an interesting tidbit because it’s a different way to stop the negativity from perpetuating itself rather than an aggressive approach. An appeal to those spreading hatred to think about what they’re doing accomplishes the same goal, and may even prove to be more effective. A not-too-subtle toss-in of the “angels” (possibly referring to those ending up like Sulli or Goo Hara) certainly is heavy enough to convince someone to think and perhaps not speak the next time they’re thinking of perpetuating a hateful message towards someone.

That Siyeon ends this segment putting forth the notion that those spreading hate will somehow feel better for doing this — that they’ll be able to “breathe again” instead of being consumed by that hatred — is just the cherry on top, a bonus that shows Dreamcatcher’s empathy for not just the victims of anonymous hate comments, but for those who for some reason spread it due to what might not be the best situation for them, either. It may be more than what they deserve, but it shows Dreamcatcher spreading a message of hope to more than just victims of abuse.

All the targets are set on you

I know about the scars you carry

Even if you don’t say a word about it

(Hold on Hold on)

Your face without any expression

It’s like you’re used to all this

(I’m knockin’ door, yeah, now I’m knockin’ door)

Can’t escape but I know

…

You look at me for no reason

Making questions that bring up more questions

But for them, guilt doesn’t exist

Part of why this message of hope and empathy has so much power is because the lyrics show Dreamcatcher, as artists in the K-pop industry who’ve been subjected to hate comments, as a bit vulnerable and able to relate to victims of this type of abuse. Gahyeon raps about what could be interpreted as feeling the heat from hate comments, yet pressing onward, at the beginning of the second verse:

Close your eyes and don’t see

Go run away from me

Even if I stumble I won’t take a step back

It’s obvious I won’t change for you, no

…while SuA has a repeated portion of the song where she speaks about being hurt herself seeing hate in the world (whether she or someone else is the target) yet wanting to act:

My heart starts to beat fast

And I can’t stop this piercing feeling

I can’t hold it anymore

I need to do something for you

he love?

Words are like thorns

They’re capable of hurting a lot

That’s why I won’t let you open that BOCA

“Dystopia” part three — what’s next?

If you’ve stuck with me this far through a ton of exhaustive, long-form analysis, you might be interested in hearing what I’d speculate is coming regarding the last portion of the “Dystopia” trilogy. The thing is, with “BOCA” promotions having just ended at the time of this writing, details are a bit scarce, though we do have a few small details from JiU and Siyeon.

In part 1 of their interview with Esquire Korea, JiU hints that the third part of the “Dystopia” trilogy will perhaps take Dreamcatcher to “Utopia”, which would be on some level an appropriate place to end the trilogy if Dreamcatcher succeeds in restoring the Tree of Language to its full strength. It would also end the trilogy on a bright note, creating a bit of symmetry with the darkness that was present at the beginning of “Scream”.

Additionally, the unboxing of the “E and D” versions of the Lose Myself album had Siyeon referring to the last word that would complete a sentence that can be gleaned by fitting the designated album versions’ letters together. “Dystopia: The Tree of Language”, containing “Scream”, formed the word “EVIL” from its four versions, while “Dystopia: Lose Myself”, containing “BOCA”, formed the word “SHED”.

There are some words you could guess at for the last album, and narrowing it down to four-letter words might make it a bit easier (even if a four-letter word isn’t a guarantee). But some ideas I have, which all play into dealing with hateful language, include:

- SHED EVIL ACTS

- EVIL SHED AWAY

- SHED EVIL EYES

- EVIL SHED FATE

As for the theme, besides a return to Utopia, I would expect that the ending of this trilogy to tie up, at least, the Tree of Language and re-create the paradise, or at least the balance, that was upset. We may see a return back to the setting of “Scream” and by the end of the music video, see the former wasteland returned to a world with light once more (it at least partially existed in the small space that was shown in shots for “BOCA”, with the partially restored tree).

With regards to Dreamcatcher’s fight against hatred, I think that even if the video buttons up the “Dystopia” story, that everyone knows the battle against hate comments and negative, awful language against others will continue. In this sense, “Dystopia” may see a return to “Utopia”, but we’ll likely hear a message, from Dreamcatcher in their own rock/pop/metal way, that an end to one fight against hate is not the end of all fights. It wouldn’t be surprising if the message was that we must be diligent in keeping watch against hatred, lest we fall into a “Dystopia” of our own doing.

Credit to the following for assistance in writing this (extremely long) article on Dreamcatcher’s “Dystopia”:

- 7 Dreamers — The end-all-be-all fansite for all things Dreamcatcher, and most critically, the site of many translated text interviews without which I would not be able to source much of the supporting information from Dreamcatcher members.

- 7 Dream Subs — One of a few major translation groups on YouTube providing a critical service to non-Korean speaking Dreamcatcher fans by subtitling Dreamcatcher content, which I was able to cite in this article.